Don’t Look Up exposes the biggest flaw in human thinking

We are not wired to 'look up'

The satirical sci-fi film Don’t Look Up is one of Netflix’s biggest hits of 2021. It tells the story of a pair of scientists struggling to convince the world that a comet will soon crash into the Earth, causing the extinction of the human species. The awkward laughs come while watching the public’s refusal to acknowledge or act on the threat. Politicians downplay the risk, the media focuses on ratings instead of reality, and tech billionaires try to find ways to monetize the comet before everyone dies. It’s an allegory for the global threats that humanity is currently (poorly) dealing with including the COVID-19 pandemic and the climate emergency.

While the critics can’t decide if Don’t Look Up is a well-made film or not, and the public is still debating the film’s potential for catalyzing public interest in tackling climate change in earnest, there is a subtle lesson in the film that appears to have escaped most people’s attention. The film reveals a flaw in human thinking that is in and of itself an extinction-level threat. It is the inability for human beings to produce a deep emotional response to hypothetical, unobservable events that will occur in the future. Despite our ability to conceive of far-future scenarios, our brains are primarily designed to deal with problems in the here and now. This disconnect—which I term prognostic myopia—features heavily in my newest book (coming out this fall). Prognostic myopia is the source of the tension (and the laughs) we find in Don’t Look Up.

In the film, the scientists are able to observe the approaching comet using radio telescopes and calculate its trajectory using mathematical calculations. There is no species other than human beings capable of engineering technology like this, or that can use math for such purposes. What’s more, there are no other species that even can imagine future events on the kind of timescale we see in the film (i.e., six months down the road). Many animals can plan their behavior for the immediate future, and some (like Western Scrub-Jays) can think about and plan for tomorrow. But only Homo sapiens can conceive of an abstract concept like “6 months from now,” let alone design and build things that will affect their lives on that timescale.

This newly evolved human capacity for long-term future-planning is generated by a host of unique cognitive skills that evolved in our species (e.g., episodic foresight, autonoetic consciousness, mental time travel) over the last quarter of a million years; skills that did not arise in our closest great ape cousins (e.g., chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas) to the same extent despite our relatively recent shared ancestry.

It’s this newness that is the problem. Humans—like all other animal species—evolved an ancient set of emotional and motivational states in our brains that drive our behavior. Hunger, for when it’s time to eat. Lust, for when it’s time to mate. Pleasure, for rewarding us for engaging in biologically relevant behaviors like eating or mating. But in almost all cases, the emotional systems in our brain driving our behavior are designed for events occurring in the moment or very soon in the future. These systems are not designed to repond to events that could happen weeks, months, or years in the future. Our biology is blind to these timescales.

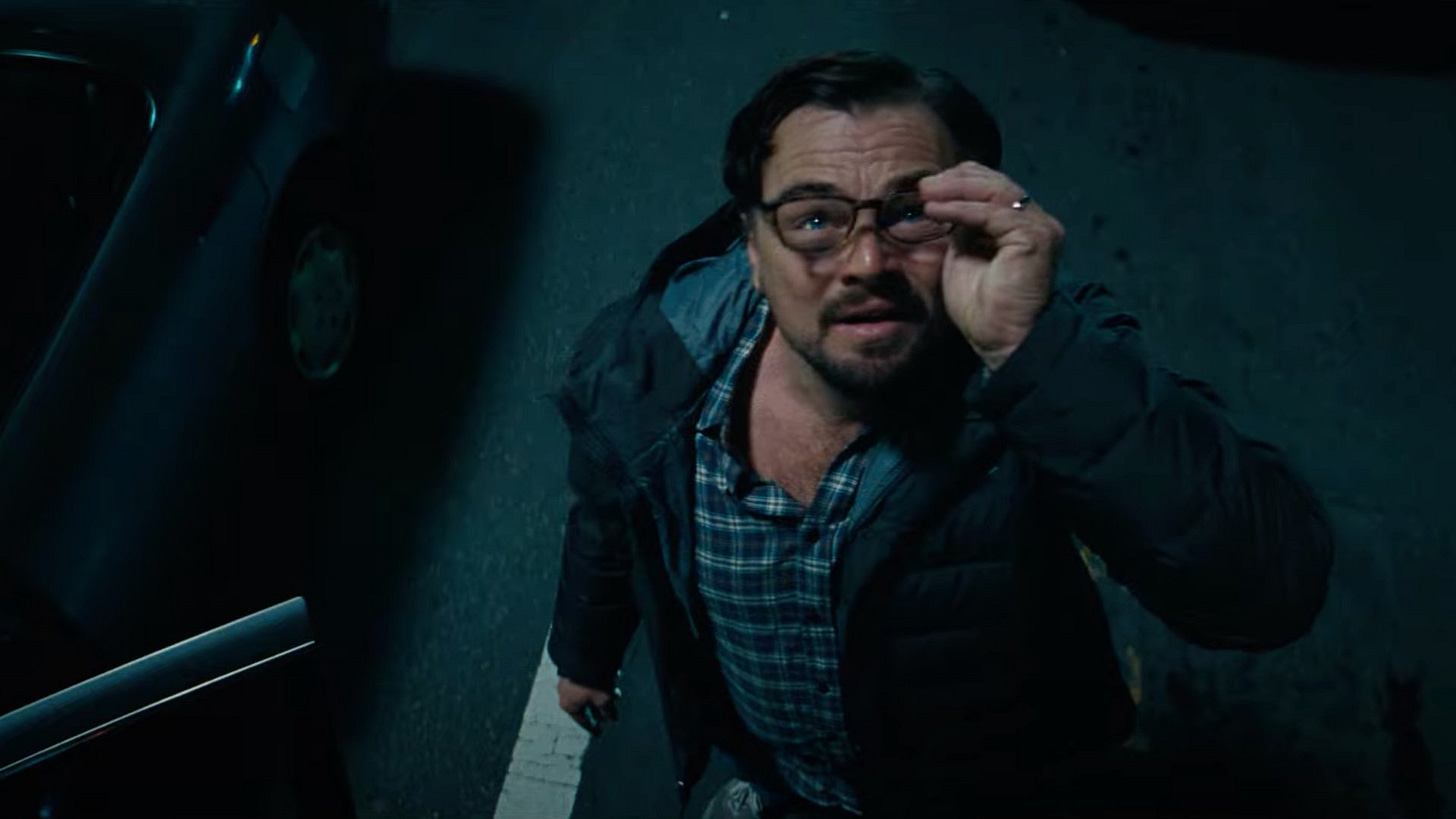

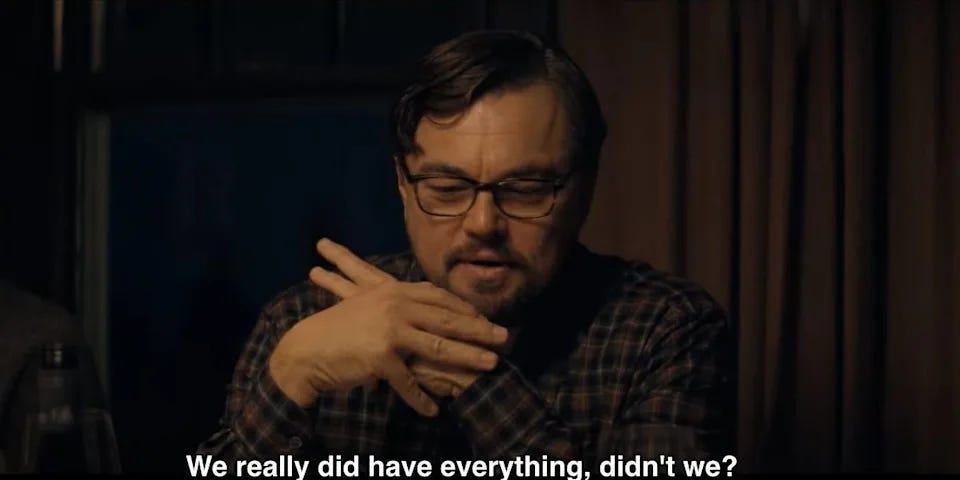

This is exactly why, when Dr. Randall Mindy (played by Leonardo DiCaprio) and Kate Dibiasky (played by Jennifer Lawrence) explain to the public that everyone is going to die when the comet hits, the public doesn’t really seem to care. And we, the viewers, understand this to be a true and accurate reflection of the human condition. The public isn’t designed by natural selection to care. The comet is not something they can see with their eyes. There is no sensory-perceptual information telling them that they are in danger. The danger is based solely on an imagined, hypothetical scenario that exists only in the mind’s eye. It is not until the moment in the film when the comet finally becomes visible to the naked eye that humanity finally looks up and sees—and thus feels—their impending doom. Then, in that moment, with a visible threat on the horizon, some people’s brains start generating an emotional response to the danger that they are in. Until then, prognostic myopia has rendered them incapable of dredging up the kind of fear and anxiety that would normally drive an animal to act. It’s the same reason why the current climate emergency does little to generate a fear response in most people. It’s too hypothetical. Too invisible. And far too long in the future until the effects become undeniably clear.

Of course, even when the danger is evident there will still be humans who deny the reality they are observing. This absurd denial—cognitive dissonance on steroids—is the source of the comedy for the second half of the film, with Meryl Streep’s character (Janie Orlean, the POTUS) telling people to literally not look up at the sky and acknowledge the comet’s existence.

This ridiculousness is something we recognize from the real world too, from those who deny the reality of climate change to those denying the existence of COVID-19. But denial, as dangerous as it is, is less of a problem than prognostic myopia. It is the period before the threat is visible—before the comet appears in the sky or COVID-19 gets in your lungs—that we still have time to act. That is what Dr. Mindy and Kate are shouting about in those months before the comet appears.

Unfortunately, as many science communicators know, no amount of shouting about far future events will get people to feel the danger that they (or their grand-kids) are in. Humans are simply not wired to have an emotional response to unseen future threats. We are, however, wired to feel sad when we see Leo and J-Law get exploded by a comet. Perhaps this will give us enough of the feels to kick-start our collective action against climate change.

Many thanks, Justin. I utterly agree with you - our cognitive response to future, especially far-ahead, threats is pretty dismal, and of course our emotional response to such threats, is essentially non-existent. The emotional part of our intelligence is, to my way of thinking, designed to be present-time and immediate, not future-oriented.

It could have been a much more effectively wake-up, but perhaps much less funny, movie if the subject matter had dealt with some ridiculously ironic/comic threat that was immediately and visually wiping out every single one of the favourite vacation resorts of the rich and famous.

Then what would need to happen for a "happy ending" is that every common Jo and Joanna would suddenly need to find it in themselves to respond in a highly loving and altruistic way, and lowly Jo and Joanna would end up saving the human race, along with all its pleasure domes and the rest of our beloved Mom Earth.

How to bring this about? Well, Dorothy has recently convinced me - the data are IN: The more oxytocin there is floating around in our atmosphere, the lighter will be our atmospheric carbon load. So we think our best hope for such a scenario is to work directly on everyone's positive vibes by stimulating the release of their serotonin, dopamine, and most especially their oxytocin. The Meryl Streep character (wait for the really absurd bit) could finally listen to some "crackpot" but actually brilliant scientist, and make it the law of the land that everyone: (1) hug and kiss and cuddle oodles of times a day in their current "cuddle bubble;" (2) hug and kiss and cuddle every animal and tree they encounter in their daily lives; (3) tell happy stories (fact or fiction) to strangers on the street and in the grocery store, not just to their children.

The scientific data we've found strongly suggests that this would utterly flood our atmosphere with oxytocin and our carbon burden would evaporate......