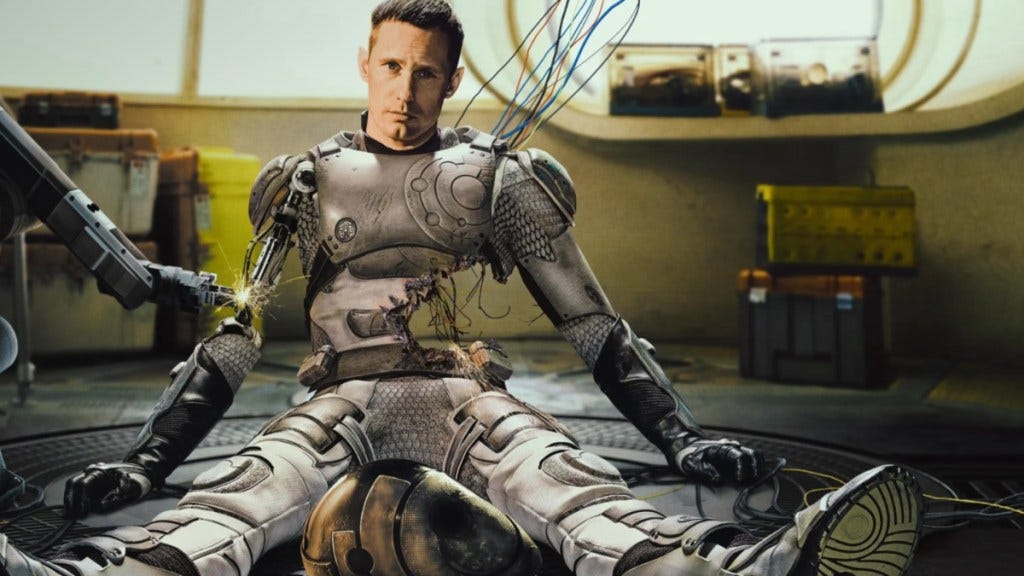

I loved Martha Wells’ Murderbot book series, and am now watching the Murdebot TV show (starring Alexander Skarsgård). I, like millions of other fans, am fascinated by stories featuring cyborgs (human/machine mashups). Nearly all cyborg stories involve the struggle between the cyborg’s thinking, feeling human mind and their cold, calculating computer programming. Famous examples are RoboCop and Seven of Nine (from Star Trek). I want to take a quick moment to explain the psychology behind why these characters are are so fascinating, and why you should care about them if you are in any way interested in science or philosophy.

Murderbot is a cyborg tasked with overseeing security for the various human groups that use him for protection. But Murderbot has been able to overcome his governor module, meaning that he is no longer obliged to follow human orders. Unlike other cyborg security units (SecUnits), Murderbot has free will. This creates an existential crisis for Murderbot who must now find a way to balance his own needs and desires (which mostly consists of him wanting to be left alone so he can watch soap operas) with the unwanted empathy toward the humans around him that is bubbling up from his human mind. The tension within the character is between the machine-like part of him that has no need for sociality or human contact, and the human-like part of his mind that is forming attachments to those around him. The humans, on the other hand, are constantly unclear as to how they should be treating Murderbot: is it just an unthinking, unfeeling machine, or should they be treating Murderbot with the same form of moral concern they apply to other humans?

As I write about in my upcoming book Humanish, the tension in the Murderbot story is something humans experience all the time; it’s generated by our understanding of the difference between how humans and non-humans (e.g., robots, AI, animals) think. As Daniel Wegner and Kurt Gray explain in their book The Mind Club, human cognitive abilities are spread across two domains: agency and experience. For a cyborg like Murderbot, the question of the extent to which his mind can generate agency and experience is what drives the story. In Murdebot’s cases, agency describes his ability (or lack thereof) to have self-control, intentions, and free will, whereas experience is his ability to be consciously aware of feelings/sensations like pleasure, desire, and joy.

Some humans in the Murderbot story wonder if, despite his cyborg nature, Murderbot might be capable of having either free will (i.e., agency) or experiencing emotions. Much of the tension in the story focuses on Murderbot’s desire to hide his true nature from those around him. The humans’ suspicion about Murderbot' s capacity for internal mental states cause them to question how Murderbot should be treated. If, for example, Murderbot can subjectively experience pain or pleasure, this might mean they have some obligation to treat him nicely, from a welfare perspective. This is not dissimilar to how humans feel obligated to treat our pets nicely, knowing that they can suffer. But if Murderbot’s cyborg nature means that he cannot experience these feelings, then this nerfs our interest in worrying about his welfare, right? Maybe not. This is where the free will/agency thing makes things a bit more complicated, and is precisely why cyborgs are such an interesting subject.

If Murderbot has a capacity for agency - a desire to do things stemming from human-like intentions - then we might feel morally obliged to worry about him. Not from a welfare perspective insofar as Murderbot cannot suffer, but from a concern for his dignity as a being with agency. Exactly why we might feel the ethical pull to take a non-sentient being’s intentions into consideration is something for ethical philosophers to fight about, but it is a natural, human response to this kind of situation.

The humans in the Murderbot story are constantly fighting with themselves (and each other) in terms of how they should be treating Murderbot, and what sorts of rights he might deserve in society. This is a common theme for cyborg-based stories, as well as stories featuring sentient or quasi-sentient AI systems or robots. And the nature of the fighting always focuses on the extent to which characters like Murderbot have minds that generate both agency and experience.

In the case of Murderbot, he himself is wresting with the problem of feeling the ethical pull to be nice/helpful to the humans because he knows that they are capable of experiencing suffering and have agency. If his mechanistic, computer software programming were in control of his mind entirely, he might be able to sidestep these feelings of moral obligation. But it is the human-ness in his reconstructed brain that is causing him to re-evaluate his relationship to those around him.

Cyborg stories intrigue us because this tension around agency and experience and what this means in terms of moral obligation is at the heart of not just how we treat robots, AI, cyborgs, or inanimate objects, but animals, nature, and even other human beings. To dehumanize another human means to, in your mind, strip them of the ability to have human-like experience or full human-like agency. This is what allows us to cause them harm/pain or even justify killing them. Cyborg stories are a way for us to wrestle with the awful feelings around dehumanization.

This is why I love science fiction stories like Murderbot. They are not just silly, escapist nonsense. They are part of a long tradition of exploring deeply philosophical concepts through the vehicle of speculative fiction. If you too like to wrestle with the problem of what it means to be human, please go read and/or watch Murderbot.